The

Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-1806), headed by

Meriwether Lewis and

William Clark, was the first

American overland expedition to the

Pacific coast and back.

Earlier European exploration to the Pacific coast In 1804, the

Louisiana Purchase sparked interest in expansion to the

west coast. A few weeks after the purchase,

President Thomas Jefferson, an advocate of western expansion, had the

Congress appropriate $2,500 for an expedition. In a message to Congress, Jefferson wrote

Louisiana Purchase and a western expedition See also: Timeline of the Lewis and Clark Expedition "Left

Pittsburgh this day at 11 o'clock with a party of 11 hands 7 of which are soldiers, a pilot and three young men on trial they having proposed to go with me throughout the voyage." they bought from the Native Americans, plus one that they stole in "retaliation" for a previous theft. Less than a month after leaving Fort Clatsop, they abandoned their canoes because portaging around all the falls proved terribly difficult.

On

July 3, after crossing the Continental Divide, the Corps split into two teams so Lewis could explore the

Marias River. Lewis' group of four met some

Blackfeet Indians. Their meeting was cordial, but during the night, the Blackfeet tried to steal their weapons. In the struggle, two Indians were killed, the only native deaths attributable to the expedition. The group of four: Lewis, Drouillard, and the Field brothers, fled over 100 miles (160 km) in a day before they camped again. Clark, meanwhile, had entered Crow territory. The

Crow tribe were known as horse thieves. At night, half of Clark's horses were gone, but not a single Crow was seen. Lewis and Clark stayed separated until they reached the confluence of the

Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers on

August 11. Clark's team had floated down the rivers in

bull boats. While reuniting, one of Clark's hunters, Pierre Cruzatte, blind in one eye and nearsighted in the other, mistook Lewis for an elk and fired, injuring Lewis in the thigh. From there, the groups were reunited and able to quickly return home by the Missouri River. They reached St. Louis on

September 23,

1806.

The Corps of Discovery returned with important information about the new United States territory and the people who lived in it, as well as its rivers and mountains, plants and animals. The expedition made a major contribution to mapping the North American continent.

Journey On

December 9,

Reaction of the Spanish The U.S. gained an extensive knowledge of the

geography of the

American West in the form of maps of major rivers and mountain ranges

Observed and described 178 plants and 122 species and subspecies of animals (see

List of species described by the Lewis and Clark Expedition)

Encouraged Euro-American fur trade in the West

Opened Euro-American diplomatic relations with the Indians

Established a precedent for Army exploration of the West

Strengthened the U.S. claim to

Oregon Territory Focused U.S. and media attention on the West

Produced a large body of literature about the West (the Lewis and Clark diaries)

Achievements

- "Seaman", Lewis' black Newfoundland dog.

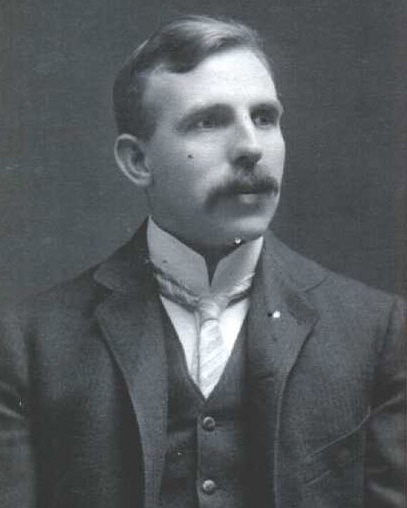

Captain

Meriwether Lewis — private secretary to President Thomas Jefferson and leader of the Expedition.

Lieutenant

William Clark — shared command of the Expedition, although technically second in command.

York — Clark's enslaved black

manservant.

Sergeant

Charles Floyd — the Expedition's quartermaster; died early in the trip. He was the one person who died during the Expedition.

Sergeant

Patrick Gass — chief carpenter, promoted to Sergeant after Floyd's death.

Sergeant

John Ordway — responsible for issuing provisions, appointing guard duties, and keeping records for the Expedition.

Sergeant

Nathaniel Hale Pryor — leader of the 1st Squad; he presided over the

court martial of privates John Collins and Hugh Hall.

Corporal Richard Warfington — conducted the return party to St. Louis in 1805.

Private John Boley — disciplined at

Camp Dubois and was assigned to the return party.

Private William E. Bratton — served as hunter and blacksmith.

Private John Collins — had frequent disciplinary problems; he was court-martialed for stealing whiskey which he had been assigned to guard.

Private

John Colter — charged with mutiny early in the trip, he later proved useful as a hunter; he earned his fame after the journey.

Private

Pierre Cruzatte — a one-eyed French fiddle-player and a skilled boatman.

Private

John Dame Private

Joseph Field — a woodsman and skilled hunter, brother of Reubin.

Private

Reubin Field — a woodsman and skilled hunter, brother of Joseph.

Private

Robert Frazer — kept a journal that was never published.

Private

George Gibson — a fiddle-player and a good hunter; he served as an interpreter (probably via

sign language).

Private Silas Goodrich — the main fisherman of the expedition.

Private

Hugh Hall — court-martialed with John Collins for stealing whiskey.

Private Thomas Proctor Howard — court-martialed for setting a "pernicious example" to the Indians by showing them that the wall at Fort Mandan was easily scaled.

Private François Labiche — French fur trader who served as an interpreter and boatman.

Private Hugh McNeal — the first white explorer to stand astride the headwaters of the Missouri River on the Continental Divide.

Private

John Newman — court-martialed and confined for "having uttered repeated expressions of a highly criminal and mutinous nature."

Private John Potts — German immigrant and a miller.

Private Moses B. Reed — attempted to desert in August 1804; convicted of desertion and expelled from the party.

Private John Robertson — member of the Corps for a very short time.

Private

George Shannon — was lost twice during the expedition, once for sixteen days. Youngest member of expedition at 19.

Private

John Shields — blacksmith, gunsmith, and a skilled carpenter; with John Colter, he was court-martialed for

mutiny.

Private John B. Thompson — may have had some experience as a surveyor.

Private Howard Tunn — hunter and navigator.

Private Ebenezer Tuttle — may have been the man sent back on

June 12,

1804; otherwise, he was with the return party from Fort Mandan in 1805.

Private

Peter M. Weiser — had some minor disciplinary problems at River Dubois; he was made a permanent member of the party.

Private William Werner — convicted of being absent without leave at

St. Charles, Missouri, at the start of the expedition.

Private Isaac White — may have been the man sent back on

June 12,

1804; otherwise, he was with the return party from Fort Mandan in 1805.

Private Joseph Whitehouse — often acted as a tailor for the other men; he kept a journal which extended the Expedition narrative by almost five months.

Private

Alexander Hamilton Willard — blacksmith; assisted John Shields. He was convicted on

July 12,

1804, of sleeping while on sentry duty and given one hundred lashes.

Private

Richard Windsor — often assigned duty as a hunter.

Interpreter

Toussaint Charbonneau — Sacagawea's husband; served as a translator and often as a cook.

Interpreter

Sacagawea — Charbonneau's wife; translated Shoshone to

Hidatsa for Charbonneau and was a valued member of the expedition.

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau — Charbonneau and Sacagawea's son, born

February 11,

1805; his presence helped dispel any notion that the expedition was a war party, smoothing the way in Indian lands.

Interpreter

George Drouillard — skilled with Indian sign language; the best hunter on the expedition.

"

Seaman", Lewis' black

Newfoundland dog.

In popular culture Timeline of the Lewis and Clark Expedition History of the United States USS Lewis and Clark and

USNS Lewis and Clark Jefferson National Expansion Memorial  Further reading Lewis and Clark Among the Indians

Further reading Lewis and Clark Among the Indians,

James P. Ronda, 1984 -

ISBN 0-8032-3870-3 Undaunted Courage,

Stephen Ambrose, 1997 -

ISBN 0-684-82697-6 National Geographic Guide to the Lewis & Clark Trail,

Thomas Schmidt, 2002 -

ISBN 0-7922-6471-1 The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged), edited by

Gary E. Moulton, 2003 -

ISBN 0-8032-2950-X The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13-Volume Set, edited by

Gary E. Moulton, 2002 -

ISBN 0-8032-2948-8 The complete text of the Lewis and Clark Journals online, University of Nebraska-Lincoln (in progress)

In Search of York: The Slave Who Went to the Pacific With Lewis and Clark,

Robert B. Betts, 2002 -

ISBN 0-87081-714-0 Online text of the Expedition's Journal at

Project Gutenberg Lewis & Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery,

Ken Burns, 1997 -

ISBN 0-679-45450-0 Lewis and Clark: across the divide, Carolyn Gilman, 2003. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books.

ISBN 1588340996

Further reading

Further reading

History

History